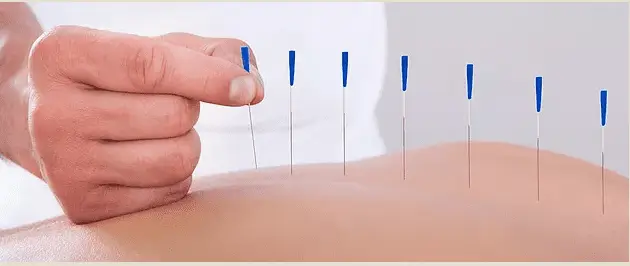

Conclusions: Several studies have demonstrated immediate or short-term improvements in pain and/or disability by targeting trigger points (TrPs) using in-and-out techniques such as ‘pistoning’ or sparrow pecking’; however, to date, no high-quality, long-term trials supporting in-and-out needling techniques at exclusively muscular TrPs exist, and the practice should, therefore, be questioned. The insertion of dry needles into asymptomatic body areas proximal and/or distal to the primary source of pain is supported by the myofascial pain syndrome literature.

Physical therapists should not ignore the findings of the Western or biomedical ‘acupuncture’ literature that have used the very same ‘dry needles’ to treat patients with a variety of neuromusculoskeletal conditions in numerous, large-scale randomized controlled trials. Although the optimal frequency, duration, and intensity of dry needling has yet to be determined for many neuromusculoskeletal conditions, the vast majority of dry needling randomized controlled trials have manually stimulated the needles and left them in situ for between 10 and 30-minute durations.

Position statements and clinical practice guidelines for dry needling should be based on the best available literature, not a single paradigm or school of thought; therefore, physical therapy associations and state boards of physical therapy should consider broadening the definition of dry needling to encompass the stimulation of neural, muscular, and connective tissues, not just ‘TrPs’.